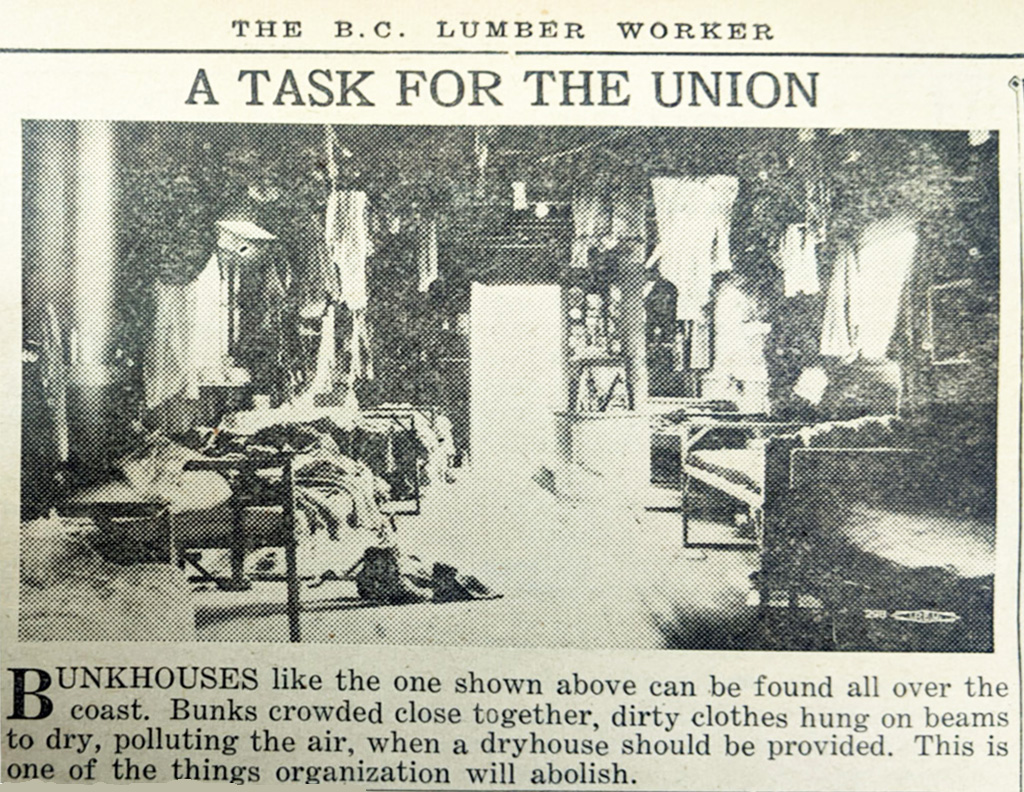

Bunkhouses and cookhouses were far from luxurious. Logging camps were temporary and transient worksites. Sawmills didn’t move around, but were industrial style operations and also included on-site bunkhouses for workers. “There is no washhouse, and the bathhouse is a long way from the bunkhouse near the sawmill,” wrote one worker at Kapoor Timber at Sooke Lake. [1]

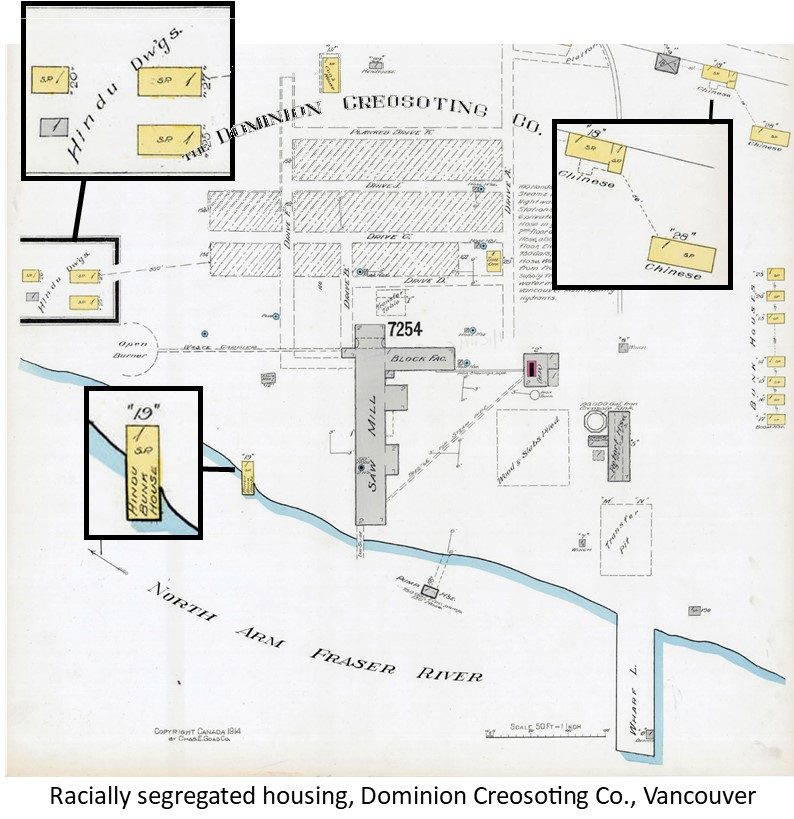

Living and cooking quarters were racially segregated. South Asian, Chinese and Japanese workers lived separate from one another; intermingling outside of work was discouraged.

“…they have no family life. After working hard on the farm or in the mill, they have no homes to which to go for the relaxation of their mind or for the expression of the softer and sweeter nature which manifests itself in the presence of wife and children. Having no chance for variety of expression, their lives are dull and monotonous until heated discussion and arguments furnish diversion.” [2]

For the South Asian community bunkhouses provided a space for political interaction. Though most early immigrants were illiterate, those who could would read radical literature in the shared bunkhouses and translate as well.

Ranjit Hall came to Canada in 1924 with his mother to join his father who was working at Fraser Mills. They were the first South Asian family at Fraser Mills and moved into the “Hindu” bunkhouses. He recalled his early life there:

“Sikhs and Muslims were living together. Bare boards. Lights were a bulb hanging down and nothing fancy. We had bunks to sleep on… There were only Chinese and Japanese who lived in other parts. We would go to the Chinese to buy some of our food. I don’t remember seeing any Chinese children, but I do remember seeing maybe 2 or 3 Chinese women… We lived right in the mill itself so there was no community. My mother contrived to make sure that I did not wander too far. She said the Chinese people love to eat little boys. This was to make me fearful so I would stay around the house. So I would afraid for a long time until I grew up and realised that this wasn’t so… the people who lived in those bunkhouses: all I saw them doing was working….”

“I was the only child, nobody suggested school to me but I understand why it wasn’t possible. There wasn’t a school nearby and I would have had to go a long distance. I could read and write Gurhmukhi very well, I had been taught in the village. I didn’t understand much of the words. I would gather some of these gentlemen outside of the cookhouse. They would sit there with their tea (this is especially on Sunday). “Bacha read something to us!” Then somebody would produce a newspaper and I would read it. I didn’t understand it, but the most popular thing was Banda Bahadur*”. [3]*Banda Bahadur was a Sikh warrior who led a successful revolt against the Mughal Empire and aimed to redistribute land from wealthy landowners to poorer agricultural workers.

- "Kapoor Wage Scale is Below Average Rates", The B.C. Lumber Worker, January 1937, 2. ↵

- Rajani Kanta Das, Hindustani Workers on the Pacific Coast. (Berlin: Walter De Gruyter & Co., 1923), 88. ↵

- Ranjit Hall, interview by Hari Sharma, Indo-Canadian Oral History Collection, August 13, 1984, sound recording, Simon Fraser University Digitized Collections, https://digital.lib.sfu.ca/icohc-53/ranjit-hall. ↵