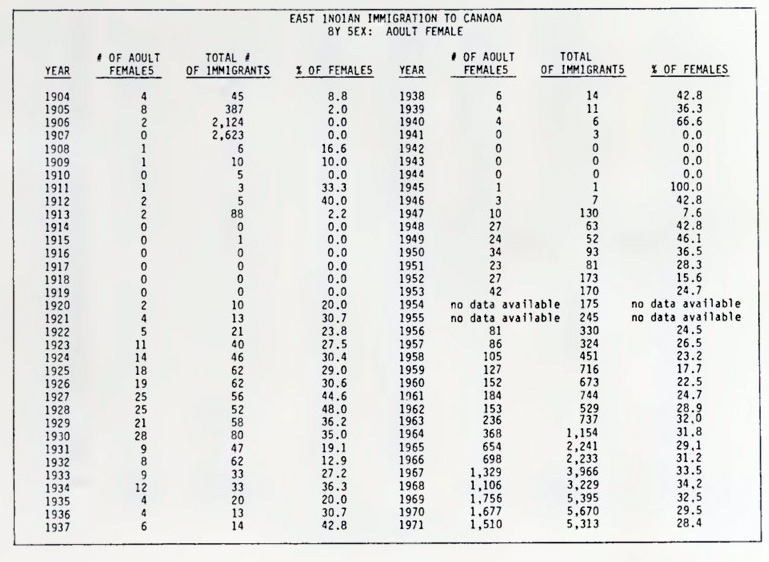

Connecting South Asian women to the early history of the BC labour movement is complicated. The total Sikh population of BC in early 1920s was 1,000; by 1925 the population was 90% male. Women and younger family members were prohibited from immigrating, so only 1 in 30 men lived with their families.

Within the IWA — like many other unions — Ladies Auxiliaries were a formidable force. The women, whose husbands were IWA members in the mills and camps, bolstered picket lines, staged marches, helped fundraise and solidified support for the union’s demands. In their communities they organized in support of better roads, hospitals, schools and children’s nutrition. In 1943 the Lake Cowichan IWA Ladies’ Auxiliary collected names on petitions to support enfranchisement for South Asians and spoke out against discrimination in the community.

“One of the things we, as members of the IWA Auxiliaries, promise to do is never turn against a person because of his or her race, creed or color…We sisters, as mothers, can play a very important part in helping to overcome racial prejudice, by teaching our children to judge the people they come in contact with, not by their color or creed, but by such things as honesty, ability and the like.” [1]

There is no evidence the IWA Ladies’ Auxiliaries included formal representation from the South Asian Community but we know the women supported the union in other ways. All women with friends and relatives working in the forest industry were fighting for the same things: a strong union and better living and working conditions.

“If you had any problem you could go to the union man and he would help you get it sorted,” said Prakash Kaur Maan. “If you pay union dues then you get [a] retirement pension. There are lots of advantages of being part of a union.”

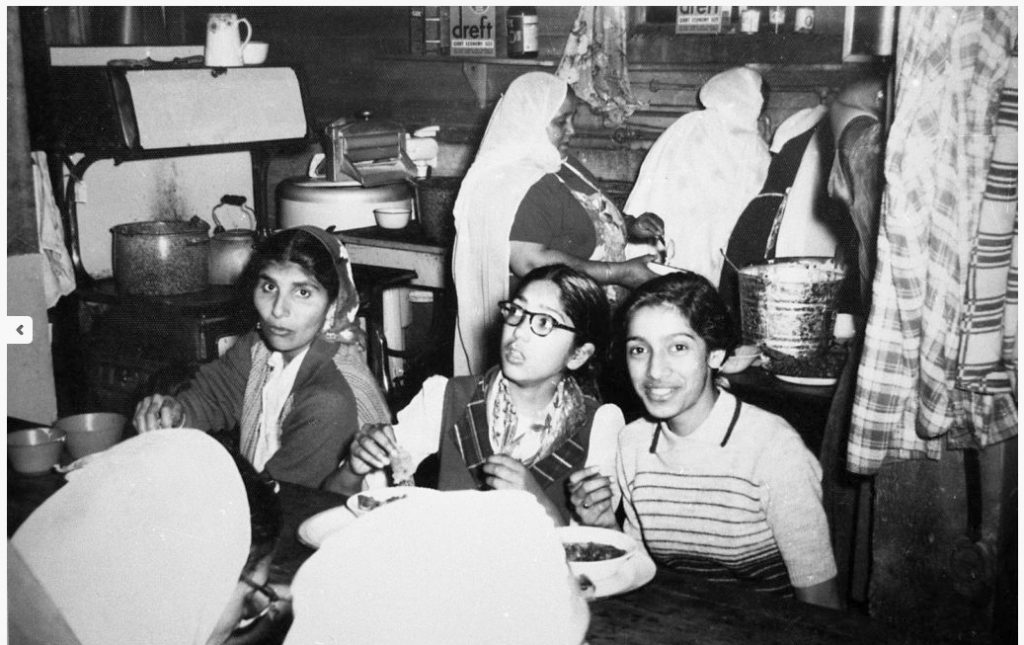

South Asian women donated food to union picket lines during the strike. “When it was the shorter strike I would bring some of my chickens and contribute like that,” said Kashmir Kaur Johal.[2]

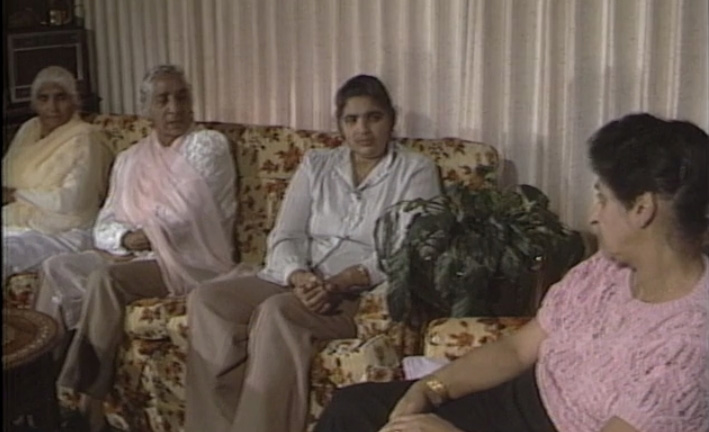

South Asian women possessed knowledge of the revolutionary past of the community. Rattan Kaur was married to the first Sikh Punjabi born in Canada. Her father-in-law was Balwant Singh, a renowned Ghadrite revolutionary and the first priest of the 2nd Avenue Gurdwara. When interviewed about her family and her life in the 1940s she turns to the women sitting next to her and says in Punjabi that he came in 1906-1907 and that this was the time of Ghadar. “They do not know all of this, do they?” she asks the others. One of the other woman replies “you just tell them that things were not good and people were not treated well back then and then he was hung.”

Jinny Sims is an activist, past-president of the BC Teachers’ Federation, labour organizer and NDP politician. This inspirational South Asian Canadian woman was elected as the MLA for Surrey-Panorama. Her father and was closely involved in the Indian Workers Association in England and had links to Ghadar’s legacy.

At the beginning of her life in Canada, she described how her place of employment was on strike. She was pregnant, was not a Canadian citizen and so was told by her union that she would be allowed to cross the picket line because of her precarious position. She thought of her father when she went home that night and decided, no matter what the consequences, she would not cross that picket line.

My dad was a member of the Anglo-Indian Workers’ Club; and anybody who knows what that is, that was basically the socialist club in India; part of the Communist Party. My dad was a comrade and very, very progressive; …[he was the] one who always encouraged me—you could do anything, is what he said. Just live your dreams, but make sure that you give back to the society. That’s where a lot of social justice values come from.

[In England] they used to have the Indian Workers’ Association meet at our house; and it was all men…there were never any women. And they would all sit, and they would talk, and some of them had graduated from universities in Moscow, but they were all Leninists, they were all wanting to change the world…they were part of the freedom fighters movement; that wanted to see an independent India, but, actually, had a vision much bigger than India. They wanted to see more equal and just distribution of wealth. They would read poetry, they would read books, they would talk about their visits to Mao’s Camp

I was given a copy of Mao’s Red Book when I was 16; really quite an amazing experience from that side.”[3]

- Helen A. White, "Race Prejudice A Subtle Poison", The BC Lumber Worker, c. 1947. ↵

- Lake Cowichan Group (Video interview), 1980s. Women's Labour History Project. Sara Diamond fonds. VIVO Media Arts Centre Archive. ↵

- Jinny Sims, interview, 2017. Past Presidents' Interview Series, BC Teachers' Federation. ↵